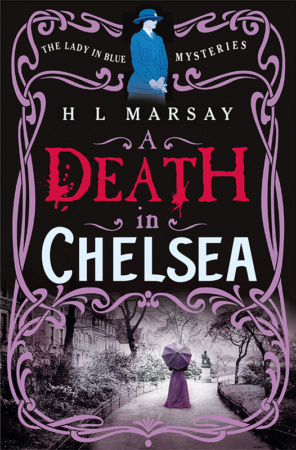

Start reading this book:

Share This Excerpt

Chapter One

“Dorothy! You must come quickly. I’ve found a dead body.” Dorothy Peto rubbed her eyes and wondered if it was possible she was still dreaming. The ringing of the telephone had woken her, and she’d stumbled out of bed and down the hallway to answer it. The longcase clock standing next to her told her it was just after six.

“Margaret, is that you?” she asked, stifling a yawn and jamming a finger in her ear so she could hear the voice at the end of the crackling line more clearly.

“Yes, please come quickly. It’s poor Mr Gaskill. He’s dead.”

“Who?” asked Dorothy but Margaret had already hung up.

Dorothy waited for the omnibus to come to a juddering halt, then stepped off on to Glebe Place with some relief. Although it was still early and a Sunday, the journey from Bloomsbury to Chelsea had been awfully hot and crowded. A taxi would have been quicker and more pleasant, but they were almost impossible to find these days. So many motor cabs had been converted into ambulances and almost all the horses had been taken for the army.

She hurried down the road and round the corner on to Cheyne Row. She checked her watch. Margaret had telephoned her almost an hour ago. She’d sounded terribly agitated. After her call, Dorothy had dressed immediately and dashed across the city.

Margaret Damer Dawson was commandant of the Women Police Volunteers, the group that she had set up with Dorothy, Mary Allen and Nina Boyle to help the regular police when war broke out. Normally, Margaret would have had Mary with her, but both she and Nina were away helping train new recruits. Over the last twelve months, the number of WPV members had grown rapidly and the women, patrolling in their dark blue uniforms, had become a familiar sight on the country’s streets. This morning, nobody gave Dorothy a second glance as she walked briskly towards Margaret’s house.

As she approached the row of smart terraced town houses, she saw Margaret hurrying towards her, accompanied as always by her three dogs: Topsy and Skip, the two spaniels, and Herbert, the basset hound.

“Oh, Dorothy, thank heavens you are here,” she gasped breathlessly.

“Margaret, are you all right? It sounded like you were saying someone had died.”

“They have! Poor Mr Gaskill. I woke early. It was so hot last night, and I never sleep well when Mary is away. So I went to open my bedroom curtains and there he was!”

“In your bedroom?”

“No, Dorothy! Of course not. In his garden. He lives next door.” She gestured to twelve Cheyne Row. It was identical to her own house, number ten. Four elegant storeys high with a basement and built of brick with black wrought-iron railings. The front door of number twelve was wide open.

“Come and take a look for yourself,” Margaret called over her shoulder as she made her way inside. Dorothy followed her through the door. The layout of the house’s interior was also the same as Margaret’s, but the décor was far more old-fashioned and a little shabby. The phrase ‘faded grandeur’ came to mind.

“Did Mr Gaskill live alone?” she enquired.

“Yes,” replied Margaret, “well, except for the servants. There’s a butler, a cook and a maid.”

They stepped out into the garden and Dorothy saw at once poor Mr Gaskill. Wearing a faded tartan dressing gown with dark pinstriped trousers beneath, he was sprawled out across the neatly trimmed lawn next to a beautifully carved stone bird table. As she got closer, she could see he was a thin, frail-looking man, who she guessed must be in his seventies. She knelt down to check for a pulse, but as soon as she touched his papery skin, she knew he was dead. Despite the heat of the early morning sun, he was stone cold. Running across his forehead was a dried trickle of blood. His still-clenched fist was full of birdseed.

“He must have come out to feed the birds,” she said.

“Yes, he does so every morning,” explained Margaret. “At seven o’clock precisely. Mary and I always joke that we could set our watches by him, but when I opened the curtains, it was half past five. I was quite stunned to see him outside already. At first, I thought the heat must have affected him too and he was simply resting. Well, you know how poor my eyesight is, Dorothy. Then I put my spectacles on and that’s when I saw him properly. I opened the window and called his name, but there was no response so I dashed over here.”

“Where were the servants?”

“They were just getting up. They thought he was still in bed. Mrs Platt the cook and Connie the maid were awfully upset. I told Duckworth the butler to take them down into the kitchen.”

“Have you telephoned the police?” asked Dorothy.

“Yes. I only spoke to a desk sergeant. The silly man asked me if I was sure I hadn’t been dreaming. Such a cheek! Anyway, I left my details and he promised to pass them on and I told Annie to try telephoning again.”

Dorothy nodded although she wasn’t convinced Margaret’s maid was the best person to enlist for such an important task. The young woman always leapt out of her skin whenever the telephone rang.

She stood up and looked around the garden. Like the house, it was almost identical to Margaret’s. It was walled on all sides with a small wooden door leading out on to Cheyne Walk, which ran along the river. There were two flower beds planted with roses on either side of the lawn and as well as the bird table, there was an equally ornate birdbath at the other end of the garden.

“Do you think he might have fallen and hit his head on the bird table?” asked Margaret. “The leather on the sole of his slipper is coming away. He could have tripped.”

Dorothy bent down. It was true. Like his dressing gown, the dead man’s slippers were old and worn, but she shook her head.

“I don’t think so. There isn’t any blood on the stone base of the bird table,” she said.

Margaret’s hand flew to her mouth. “Oh my goodness,” she gasped. “Then you think someone may have attacked him. How dreadful! In his own garden. And this is such a nice, quiet neighbourhood. Who could have done such a thing?”

“A burglar perhaps? They could have come through that door at the bottom of the garden. I wonder if it’s locked.”

Dorothy was about to go and check, when in the distance, she could hear the unmistakable ringing bell of an approaching police car. “It sounds like Scotland Yard got your message after all. I’ll go and tell the servants to prepare themselves to be interviewed. You stay here with the body and, Margaret, do keep the dogs away,” she said, pointing to Herbert, who was trying to eat the birdseed out of the dead man’s hand.

She quickly made her way back inside the house and down the stairs that led to the kitchen. Sitting around a well-scrubbed pine-topped table were the three servants. A man of about sixty with greying hair and a ruddy complexion, a plump woman of a similar age and a young woman with her dark hair tied in a bun, who was sobbing into her apron. They all rose to their feet when Dorothy opened the door.

“Hello,” she said. “My name is Miss Dorothy Peto. Do please sit down. I am a friend of Miss Damer Dawson. I’m so sorry about Mr Gaskill, but I wanted to let you know the police will be arriving shortly. They will probably want to speak to each of you.”

The young woman’s face turned as white as alabaster. She gripped hold of the table and looked like she might faint at any second.

“The police!” she cried. “Why do I have to talk to them? I won’t be able to tell them anything.”

“Calm down, Connie,” ordered the man. He nodded to Dorothy. “I’m Duckworth, the butler, miss. This is Mrs Platt, the cook, and Connie Beal, the parlour maid. It’s good of you to come and tell us about the police. As you can see, we are all very upset about poor Mr Gaskill.”

Connie began sobbing again. Dorothy placed a hand on her shoulder.

“Don’t worry. They will only want to know if you saw anything that might help them. If you would like me to, I’ll sit with you while you are questioned,” she offered. Before war had broken out, she and Nina had been campaigning for women and children to be treated more fairly by the justice system, including being allowed to have another woman present when they were being interviewed. “Please sit down,” she repeated. “Let me make you all some tea.”

Only Connie sank back down into chair. Duckworth and Mrs Platt exchanged a concerned look as Dorothy picked up the kettle that was bubbling on the stove.

“You don’t have to do that, miss,” said Mrs Platt. “It doesn’t seem right.”

Dorothy turned and smiled at her as she reached for some cups from the dresser.

“Not at all. I’m happy to,” she replied.

The cook smiled back and bustled through into the pantry. “Then I’ll fetch us some cake, miss.”

“I can do that,” Dorothy called after her.

“You are wasting your time, Miss Peto,” said Duckworth, straightening his tie. He pointed to his ear. “She’s as deaf as a post. No tea for me thank you, miss. I think I’ll step outside for a breath of fresh air before the police officers arrive.”

He walked a little unsteadily out of the kitchen, leaving the three women together. Dorothy made the tea, while Mrs Platt cut three thick slices of madeira cake and Connie eventually stopped crying.

“How long have you worked for Mr Gaskill?” asked Dorothy as she settled into the chair opposite the cook.

“Nearly twenty years, miss. Mr Duckworth is the same and Connie here has been with us for just over a year now.”

“What sort of an employer was he?”

Dorothy saw Mrs Platt catch Connie’s eye before she replied.

“Fair but firm I’d say, miss. That’s the best way to describe the master. Fair but firm.”

Dorothy glanced over at Connie who nodded in agreement, her eyes cast down.

“His death must be a terrible shock for you,” continued Dorothy.

“Oh it was,” replied the cook. “I thought the master was still in bed. He usually rises at half past six. He gets dressed then comes down to the library. Then he goes to feed the birds so he can watch them while he has his breakfast. I’d come down to the kitchen at my usual time and was about to start making the tea and boiling his eggs—he always started the day with two boiled eggs—when Miss Damer Dawson started hammering on the front door and shouting.” She paused and took a sip of her tea. “The next thing I know, Mr Duckworth is down here telling me that the master is dead in the garden.”

“Where were you, Connie?” asked Dorothy, as the maid finally seemed to have calmed down.

“I was in the library, miss, tiding up and emptying the grate before the master came down. Except of course he didn’t come down.” She paused to dry her eyes on the edge of her apron. “I heard Miss Damer Dawson come to the door and I opened the curtains in the library just as she and Mr Duckworth went into the garden. That’s when I saw poor Mr Gaskill lying there on the grass.”

Mrs Platt reached over and patted her hand, but Dorothy frowned.

“Did Mr Gaskill always have the fire lit in the library? It’s been awfully hot all week.”

“No, miss,” agreed Connie. “It hadn’t been lit for over ten days, but he rang the bell yesterday for me to go and light it. It was just after Mr Duckworth had taken him the second post.”

“Did he say why? Was he ill? Did he have a chill?”

“No, miss. I don’t think so but…” she looked quickly at Mrs Platt “…he seemed a bit out of sorts all day yesterday. All he said was ‘light the fire please, Connie’.”

“I see, and when was the last time you both saw Mr Gaskill alive?” asked Dorothy. As she was talking to the two female servants, she realised that Duckworth, the butler, was correct. Mrs Platt was taking part in the conversation quite easily, but her eyes were always on the lips of whomever was speaking. Before she answered now, she exchanged another quick look with Connie.

“It was late morning, miss. I’d gone up to discuss the evening’s menu with him.”

“Did he dine alone last night?”

“No, miss. Mr Gerald Gaskill was here. He’s the master’s nephew. They usually dined together on a Saturday evening,” Mrs Platt explained, then gave Connie a nod of encouragement.

The maid gave a small cough before she spoke. “I last saw the master just after supper, yesterday evening, miss,” she said, her eyes fixed on the hem of her apron as she fiddled with it. “I was beginning to clear the table in the dining room as the master and Mr Gerald were going through into the library. I offered to go and close the curtains in there for them as it had grown dark, but Mr Gerald said not to worry and that he would do it. Then I returned to the kitchen, helped with washing the dishes and went up to bed the same time as Mrs Platt. Our bedrooms are in the attic.”

“So you both passed the library on your way to bed?”

“No, miss. We used the back staircase not the main one.”

“Did Mr Duckworth retire at the same time as you?” asked Dorothy, topping up the cook’s cup. Connie’s tea and cake remained untouched.

“No, he would be waiting for Mr Gerald to leave. He was in his pantry across the way there. I wished him goodnight, but I didn’t hear him come upstairs,” explained Mrs Platt pointing through the open door to another closed door opposite the kitchen.

“Did Mr Gaskill have any other visitors yesterday?” enquired Dorothy.

“Yes. Mr Pearson. He’s Mr Gaskill’s solicitor. Mr Gaskill sent for him. He arrived at three o’clock—I made a tray of tea for Mr Duckworth to take up—and he left at around five o’clock,” said Mrs Platt.

“I don’t suppose you know why his solicitor was visiting Mr Gaskill?” Dorothy had addressed her question to Connie, but it was Mrs Platt who answered, shaking her head with a smile.

“No, miss. It wasn’t our place to know the master’s business.”

Dorothy nodded although privately she thought the servants almost always knew exactly what was going on. Upstairs, she could hear the sound of heavy footsteps. The police had clearly arrived. She should really go and speak with them.

“I see. Well, thank you for the cake, Mrs Platt. I should be going now, but I promise I’ll be here if you need me when the police interview you.”

Both women murmured their thanks, as Dorothy rose to her feet and left the kitchen. When she returned upstairs, there was no sign of Duckworth but she found a uniformed policeman now standing guard by the still-open front door and several more out in the garden. Standing next to Margaret and looking down at the body was a tall man in a navy suit, leaning on a walking stick. He turned at the sound of her footsteps and raised his hat.

“Good morning, Miss Peto. I was wondering when I might see you,” he said. It was Inspector Derwent of Scotland Yard. Dorothy had met him before, when he’d been investigating the death of two actresses. The scar across his face and his stern demeanour made him seem rather forbidding, but Dorothy had grown used to his ways.

“Oh, Dorothy, there you are,” exclaimed Margaret. “I was just explaining to Inspector Derwent that I telephoned you after I called Scotland Yard.”

“Yet, you managed to beat us here, Miss Peto.”

“Well, it was obvious from Margaret’s call that this was a matter of urgency, but it seems the officer Margaret first spoke with was disinclined to believe her story, so perhaps that caused your delay,” suggested Dorothy sweetly. “We wondered at first if he could have fallen and hit his head on the bird table, but there’s no blood on the base.”

“No,” replied the inspector, shaking his head, “and unless I’m very much mistaken, he has been dead for several hours. We’ll know more when Willerby and Dr Stirk arrive. I take it he wasn’t in the habit of wandering around his garden in the early hours of the morning?”

“No,” replied Margaret. “As I said, he usually doesn’t come out until exactly seven o’clock.”

“Have you known the deceased long, Miss Damer Dawson?” asked the inspector.

“We’ve been neighbours for almost ten years—that’s when I moved here—but I wouldn’t say I knew him, Inspector. He was a bit of a recluse. Occasionally, we would meet on the street when I was walking the dogs. He was a great animal lover too. No matter the weather, he would always put seed out for the birds.”

The inspector didn’t look particularly impressed by this piece of information. He knelt down next to the body and carefully raised the left sleeve of the dressing gown.

“Can you recall if he wore a wristwatch, Miss Damer Dawson?” he asked. Dorothy peered down.

“He isn’t wearing one now,” she commented.

“No,” agreed the inspector, “and I would have expected a man of routine to have one.”

Margaret’s face was creased in concentration. “Let me think now. No, he had one of those old-fashioned fob watches on a chain. It was a gold one. He always used to check it just before he returned to the house. I remember my father had a similar one. He kept it in his dressing gown pocket. Mr Gaskill that is, not my father,” she explained.

Inspector Derwent felt in first one of Mr Gaskill’s pockets and then the other. “It’s not there now,” he declared as he stood up straight again.

“If he was attacked, could theft of the watch be the motive?” asked Dorothy.

Before the inspector could reply, one of the uniformed officers, who was near the birdbath shouted out, “Sir! I think we’ve found something.”

Skip and Topsy, Margaret’s two spaniels, immediately charged through the flower bed towards the constable.

“Miss Damer Dawson, you have been extremely helpful but could I please ask you to remove your dogs from the garden?” asked the inspector as he made his way towards the birdbath.

“I’m so sorry, Inspector Derwent. They don’t mean to get in the way. They only want to help too, you understand,” insisted Margaret.

“I’m sure that is true, Miss Damer Dawson, but the ground is bone dry. My men will find it difficult enough to look for footprints without their assistance,” replied the inspector grimly.

“Margaret, why don’t we take them down to the river. They must have missed their morning walk in all the excitement,” suggested Dorothy. She would have loved to stay at the scene and see what the constable had found, but the expression on Inspector Derwent’s face and the way his fingers were drumming against his bad leg told her his patience was due to run out very soon. With a sigh, Margaret reluctantly agreed.

End of Excerpt