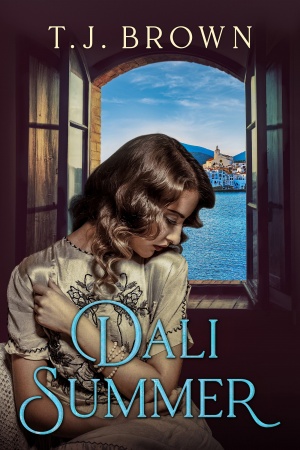

Start reading this book:

Share This Excerpt

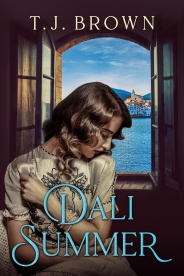

The Cadaqués library might have been overlooked by the casual observer, had it not been for the window boxes filled with extravagant red carnations. The librarian, as nondescript as the library, tended the flowers, watering, fertilizing, and clipping off the dead blooms with care. Occasionally, after looking around to make sure she wasn’t being observed, she would lean close and breathe in their subtle, spicy aroma. The scent and not their color was the reason she kept them, for the librarian was color-blind and had been since the age of six when she’d been hit on the back of the head with a crystal paperweight.

Occasionally, Dolors, the unlucky librarian in question, would be tempted to pluck a bloom and tuck it behind her ear so as to carry the scent with her, but she always resisted this impulse. It would look ridiculous and, above all, she mustn’t make herself ridiculous.

The sun glinted off the whitewashed walls of the library as Dolors locked the door with a practiced twist of her wrist and strolled down the narrow main street of Cadaqués with sedate, measured steps. The breeze, fresh off the bay and filled with the salty scent of the day’s catch, kept the heat down to a tolerable level. Occasionally, a shopkeeper, out sweeping his step or washing a display window, would call to her and Dolors would reply with a polite nod of her head.

They didn’t much like her.

Whether they liked her or not was immaterial as long as they respected her. As long as she was never the subject of gossip during the long lunches the residents shared at the various cafes about town. Dolors conducted herself at all times as if someone were judging her behavior, and while it wasn’t a comfortable way to live, no one could say that her reputation wasn’t impeccable.

Riotous feminine laughter interrupted the quiet street and Dolors turned her head to see where the noise was coming from. Her eyes widened to see the shine of an automobile making its slow, tortured way through narrow streets best left for pedestrians and donkeys. The vehicle had no top, which was even more surprising, but most astonishing of all was the woman kneeling on the hood of the car and directing the driver with shrieks of hilarity. Dolors frowned at the sight, wondering why they were in this part of town. Motorcars were still a rarity in Cadaqués, and the few that made their way into town tended to stick down near the waterfront where the streets were wider.

“Xavi! Slow down before you lose me completely!” the woman cried.

Mirth punctuated her words, as if riding on the hood of an auto was the most wonderful thing in the world instead of something so unseemly Dolors could only stare, her lips pursed in disapproval. Summer people.

The woman’s dress had ridden up, showing flashes of shapely ankles and calves. A long motoring scarf wrapped around her head and splashed across the hood of the auto like a waterfall, but in spite of its length, it couldn’t contain the unruly curls that sprang out from underneath. The man sped up and then swerved around the corner, while the woman screeched and rebalanced herself. Peals of laughter issued from both the driver, a man whom Dolors barely noted, and the woman perched audaciously atop the car like an ornament. Around them shopkeepers and women out marketing stopped and stared but the woman didn’t seem to notice the spectacle she was making.

The hum of the engine faded as the motorcar presumably made its way down to the more hospitable beachfront.

Everyone else turned back to their business but still Dolors stood uncertainly in the street. An unnamable emotion surged over her, rooting her feet to the ground. The woman’s carefree laughter echoed in her ears and filled Dolors with an acute longing she couldn’t describe. Had Dolors ever laughed like that? Done anything so outlandish?

No.

But the sight of the audacious woman lingered in her mind like the fragrance of bougainvillea on the air. What would it be like to do such a thing? To be so unfettered that she could climb atop a motorcar while it was driving, show her legs and laugh about it?

Dolors straightened her shoulders and turned back toward her destination. Such antics were not for her. She pushed the troubling incident from her mind and continued on her way. Her habits were as much a part of her as her color blindness and she rarely let anything deter her from them. Certainly not the ridiculous shenanigans of a woman she didn’t even know.

The strange, noisy incident struck a memory in the minds of some of the more elderly citizens in the street. As Dolors passed by, they recalled that just thirty years earlier in the spring of 1887, Dolors’s beautiful mother, Gemma, had created a similar stir. It was doubtful, however, that Gemma was as concerned with her reputation as Dolors was—her character had already been destroyed by the arrival of the toddler she held so carefully in her arms.

At that time, people had stopped and stared, for Gemma had been gone for almost two years after being at the center of a scandal that involved a young man from a leading family.

Usually, an unexpected pregnancy was followed by a hastily arranged marriage, brought about by the girl’s family and an irate priest but motherless Gemma’s drunken father was too incoherent to speak for her. The boy’s family forbade the marriage and the girl was bundled hastily off in the middle of the night with a few gold coins in her hand.

Now Gemma was back, dressed in a white lace gown, with flowers in her hair. People were as astonished by her fresh young beauty as they were her appearance. Why would such a girl carry the product of her shame with such dignity through the center of Cadaqués? Why had she returned? What could it mean?

Word of Gemma’s reappearance spread more quickly than her actual walk through town. Old women, clucking in horror and delight, threw scarves over their heads and joined her. Shopkeepers locked their doors and trailed after them, eager to see what would happen. Children, recently released from school, cavorted alongside the procession with their sticks and hoops, thinking, in their innocence, that it was an impromptu parade.

Gemma seemed oblivious to the sensation she was creating as she wound her way through the town’s narrow streets and passed St. Mary’s church, where the priest had once called her a whore. The baby Dolors, not yet two, waved her fat fists and smiled indiscriminately at the people around her. Like her mother, she wore white lace, only slightly stained in the front with spittle. The child’s beaming face seemed at odds with the carefully blank expression on her mother’s exquisite features.

Gasps came from the crowd as they realized Gemma was making her way to the Posa family estate, the home of the young man who had gotten her in the family way. The tiny fishing village of Cadaqués had never experienced such scandal as was about to occur. How would Doña Maria, the iron-fisted matriarch of the family react? What was Gemma doing, marching her illegitimate issue up to the front door of the Posa casa?

As luck would happen, Doña Maria was sitting with her sister and two of their servants snapping beans on the front patio under a bower of bougainvillea. The woman frowned as she spotted the procession over the low wall of the garden and rose to her feet. The people held their breath as Doña Maria stepped forward to greet them, her cold eyes scanning the crowd, looking for the meaning behind the unexpected visit.

Only then did it seem that Gemma faltered, pausing a moment before the woman who had played such a central part in the destruction of her life. But then she drew back her shoulders and moved forward. Before Doña Maria had time to react, Gemma had marched through the gate and placed the baby in the surprised woman’s arms.

The infant reared back and stared at the old woman and the old woman stared back, horror crossing her features. For a moment an incredulous hush fell over the crowd before one old crone whispered, “Look. The baby has Doña Maria’s nose.”

A titter went through the crowd for it was true. The prominent, sharply hooked nose of the matron sat in miniature on the baby’s face. It was too important of a nose for an infant to carry and she wouldn’t grow into it for years, but the likeness was amazing and the tittering soon grew into laughter.

Wordlessly, Gemma disappeared back into the crowd. With their eyes on Doña Maria, no one in the laughing crowd noticed the young woman’s swift departure.

Nor did anyone mark her desperate flight to the cliffs of Cap de Creus, or witness the leap that dashed her fragile body onto the rocks below. Not until fishermen found her, her beautiful white lace drenched in blood, did anyone know what had happened to her.

Thirty years later, the result of that shameful tragedy now walked the same narrow streets, going to the very same home high on the hill. The differences, however, were marked. Where lovely, disgraced Gemma was small and delicate, Dolors most definitely was not. She stood almost tall as a man, with long limbs and large capable hands. Her abundant black hair was pulled back into a plain, severe bun, revealing unremarkable facial features, already set into the unsmiling lines that she would wear into old age if she wasn’t careful. Her nose, the uncompromising Posa nose, gave her a haughty look that she cultivated to keep people at bay. The only features she inherited from her beautiful mother were expressive dark eyes and a mobile, passionate mouth that she kept pressed into a straight, inflexible line.

Unlike her mother, however, Dolors stopped at a small, plain building next to the whitewashed glory of St. Mary’s church.

She’d barely knocked on the door before it opened.

“You’re late,” a small nun in a white habit chastised. “Your tea is almost cold.”

“You English and your tea,” Dolors said as she entered the small, dim interior of the nun’s quarters. “One would think you were married to the tea, rather than to God.” She spoke lightly, humor softening the sarcastic words.

“I gave tea up for Lent once and regretted my sacrifice daily. I won’t do it again, unless of course, that’s what God wants me to do.”

“And how would your God tell you if he wanted you to give up tea? By post? Or does he have a more direct line?” Dolors asked, her voice innocent as she sat at a rickety table.

The small nunnery owed as much of its cool interior to being in the shadow of the giant church as it did to its thick walls and Dolors relished the respite.

The young nun wagged her finger. “No, you don’t. You won’t get me into a theological argument today. I want to know what you thought of the book.”

“Ah, the book.” Dolors took her cup of tea and the plate of English biscuits with a smile of thanks and watched as the nun finished setting the tiny kitchen to rights before continuing.

Sister Mary Agnes finally sat across from her and nodded. “Yes, the book.”

“How long have you been teaching me English?” Dolors asked.

“Two years.”

“And we are friends, yes?”

The nun nodded, her face bemused. “Of course. Father Miguel introduced us because he was afraid for your soul and wanted me to improve my Catalan. Unfortunately, I think my Catalan has improved more than your soul.”

Dolors agreed. “My English, too. In fact, I thought I was on my way to becoming fluent until you gave me that book. I almost threw it off the docks and into the bay. If that’s English, than what in God’s holy name have you been teaching me?”

The nun set down her cup and laughed until tears streamed down her face. When she’d wiped her eyes and took a recuperative sip of tea, she asked, “I take it you didn’t find Beowolf to your liking?”

“It was a ridiculous fairy tale.” Dolors dismissed the English classic with a wave of her hand. “And if that’s English, I’m as much of a nun as you.”

The nun smiled. “And we both know that isn’t true.”

Dolors bit into the thin, delicate biscuit that were her friend’s special weakness. “I thought about being a nun once,” she confessed.

Sister Mary Agnes’s brows rose to the top of her habit. “And what happened?”

“It would have made my family too happy,” she answered dryly.

Sister Mary Agnes was the only person on earth that Dolors would have said this to. The two women, as different by temperament as they were by vocation, were friends and as Dolors’s only friend, Sister Mary Agnes knew more about the strange workings of Dolors’s family than anyone.

The nun cleared her throat as if wanting to say something and Dolors waited.

“The father is worried about Bernat,” Sister Mary Agnes said.

Dolors stiffened, the sweet biscuit turning to dust in her mouth. “Bernat is fine.” She paused. “Why is Father Miguel worried?”

“Your little brother is becoming wild. Most of his friends spend more time drinking wine in the cafes than out on the bay.”

Dolors shrugged, her chest tight. “They’re little more than boys and it’s a bad year for fishing.”

“But they don’t even try,” the nun insisted. “And Bernat is not a fisherman. The foreman at the factory told Father Miguel that he’s missing shifts at work.”

Dolors sipped her tea. Her own concern for Bernat was too fresh to discuss with anyone else, even with her friend. Just last week, she’d seen Bernat driving a motorcar that didn’t belong to him up toward the mountains. The vehicle had been full of his lazy friends, and later she heard it had been stolen and found wrecked near Port Lligat. When she confronted Bernat with her knowledge, he had shrugged it off with a careless laugh. But this was something she couldn’t tell the sister, no matter how much Dolors valued her companionship.

A small insistent headache began to throb at the base of Dolors’s skull as if the old injury was new again. “Bernat is young. He’ll grow out of it.”

“The talk in the cafes of a free Catalonia is becoming more strident,” the nun said. “The father is worried because much of it is coming from Bernat’s friends. You know how young men are.”

Dolors dismissed her friend with a wave of her hand. “There has always been talk of a free Catalonia. It’s just talk.”

The sister leaned forward, her eyes serious. “But Spain has never been so unstable before. If the young men of Cadaqués join up with the young men of other villages and the radicals in Barcelona, it could be disastrous. There is even talk of a worker’s union.”

Dolors swallowed. The sister was right, of course, but she still had a difficult time believing that indolent young men who would rather drink wine and play music in the cafes than work could be induced to rebel. “I’ll talk to him,” she said, her voice as stiff as her posture. “Now I must go.”

A frown line appeared between the sister’s eyes. “I’ve offended you. I’m sorry. I know how much you love your brother. That’s why I mentioned it.”

In an uncharacteristic gesture of affection, Dolors reached out and patted her friend’s hand. “Don’t worry. I’m not offended. Bernat will be fine.” She rose to leave.

“But you haven’t even given me my book yet!”

“You’re right.” Dolors reached into her bag and pulled out a large book. The nun recoiled.

“That’s not a book, that’s a weapon!” she cried.

Dolors laughed. “You’re right in more ways than one. It’s Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy. Have you heard of the author?”

Sister Mary Agnes nodded. “Of course. How ironic that I’m reading a Russian novel in Spanish.”

“Life is full of ironies. Adios.” Dolors continued up the street to the path that led to her casa. The same path her mother had taken, attended by an entire village that had unknowingly participated in a death march.

The same path that led to where Dolors lived with the woman responsible for her mother’s death.

End of Excerpt