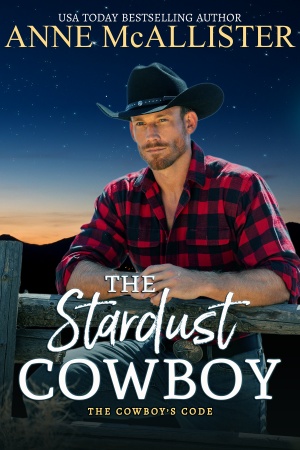

Start reading this book:

Share This Excerpt

Jake Malone was bored out of his skull.

Why should he have to spend a whole sunny June afternoon and half of a perfect star-studded night sitting through a wedding? It wasn’t like he was the one getting married! It wasn’t like he even had to carry the ring or sing in the choir or do anything. He just had to sit.

He’d been sitting for hours.

The only other wedding he’d been to—his aunt Milly’s last winter—had been pretty cool. And interesting. And short.

Real short.

In fact, it had ended up not being a wedding at all, because right in the middle of the ceremony Cash Callahan, Aunt Milly’s old boyfriend, had stopped it. He’d socked the usher who’d tried to stop him—and then Aunt Milly had socked him!

Now, that had been worth watching!

It was the reason Jake hadn’t minded when his mom had dragged him to this one. Even though she’d said, “Don’t get your hopes up,” Jake couldn’t help it. After all, Shane Nichols, the groom, was usually as interesting as Cash was, and Poppy, the bride, had reddish-brown hair and Jake’s grandpa always said redheads were unpredictable.

But no old boyfriends of Poppy’s had come storming down the aisle. No one had punched anyone else. Shane had been on his best behavior all day and Poppy had been all smiles. Even Milly and Cash, who hadn’t been on the best of terms since that earlier wedding, weren’t fighting today.

In fact they were standing in the middle of the dance floor, staring into each other’s eyes like they were in some sappy movie. Jake looked away, disgusted. Nothing exciting was happening at all.

It was so bad that eventually even Shane and Poppy got bored and left.

“How come they get to go first?” Jake asked his mother as everyone gathered to throw birdseed and glitter on Shane and Poppy as they escaped.

“It’s tradition,” his mother explained.

Jake thought it was time to start a new tradition.

“Mom,” he said plaintively. “Can we go now?”

“Not yet, dear.” She patted his shoulder but didn’t even look at him. She was shifting from one foot to another in those high heels she almost never wore while she tried not to yawn in Russ Honnecker’s face.

Now Jake watched worriedly as ol’ Boredom Honnecker cranked up the charm. Jake knew his mother wasn’t getting any younger, and he supposed she might want a husband. Women did, he’d heard.

But, good grief, not Russ Honnecker!

There was no way Jake was going to have Russ Honnecker as a dad!

He snuck out his toe and kind of nudged his mother’s leg. She stepped away, nodding at whatever Russ was saying. And nodding. And nodding. Jake thought she looked like one of those stupid dolls with the wobbly heads.

“Mommmmm.”

Her hand came down on his shoulder and squeezed. Hard. Jake shrugged away. And then the music started again, and Jake’s mom said, “Why, of course, Russ.” And the next thing Jake knew Russ had taken her into his arms.

“Mommmmm!”

She turned in Russ’s arms and shot a look like a dagger over Russ’s shoulder. “Behave,” she mouthed.

Jake glared at her mutinously. Behave? Behave? What’d she think he’d been doing for hours? He glared back at her, then swung around and up on his knees to stare out the window into the darkness.

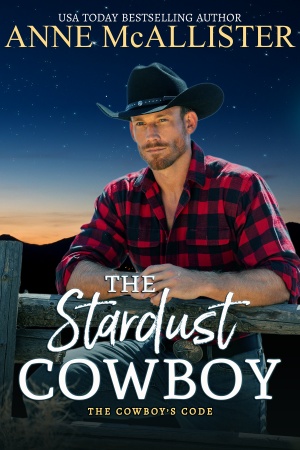

And that was when he saw the cowboy under the streetlight.

Cowboys weren’t unusual in Livingston, Montana. Jake saw them in the stores and on the street. He saw them in battered pickups on the Interstate. He sometimes even glimpsed them working cattle when he and his grandpa went fishing up the valley. He even knew one pretty well. Cash, Aunt Milly’s boyfriend, was a rodeo cowboy, or he had been until he’d gone to work for Taggart Jones and Jed McCall. He was even doing something for Poppy’s dad’s new horse-breeding business. Jake guessed Cash was more of a regular cowboy now, but that was good enough for Jake.

He had been fascinated with cowboys ever since his aunt Milly had taken him to a rodeo when he was two years old. They seemed bigger and brighter than ordinary men like his grandfather, who ran a grocery store, or Mr. Hudson, who was retired from the post office and mowed his lawn five times a week, or Russ Honnecker, who was the most boring person on earth.

Cowboys weren’t boring.

Except at weddings, apparently, when they were expected to behave, too.

Jake pressed his face to the glass to study the cowboy under the streetlamp. He wasn’t at the wedding, so maybe there was hope for him.

He looked just like any other cowboy. Blue jeans. A long-sleeve shirt. Boots. A summer straw cowboy hat shadowed his face from the light above so Jake couldn’t see him all that clearly.

He was leaning against the lamppost, one thumb hooked in his belt loop. As Jake watched, he rubbed his shoulders against the lamppost and studied the building where Jake was.

Jake’s interest quickened. He felt a stirring of hope.

Maybe the cowboy was one of Poppy’s old boyfriends, come to stop the wedding and punch Shane in the nose.

But even as he speculated, Jake’s hopes died. Whoever he was, the cowboy was too late for that. The wedding was over; he couldn’t stop it. And Shane and Poppy were already gone.

If he was going to punch Shane, he’d have to find him first. And Jake wouldn’t be around to see it.

The cowboy rocked on his heels and continued to stare at the building. He took a step toward it. Then he stopped and rubbed a hand against the back of his neck before leaning against the lamppost again.

What was he waiting for? Why didn’t he just come in?

The cowboy scuffed his toe against the concrete. A tiny arc of sparkly light shot up from his boot. Jake’s gaze jerked.

What was that? He pressed his forehead against the glass.

The cowboy shoved himself away from the lamppost. Jake straightened, watching intently, waiting for him to come up the steps.

Instead, tucking his hands into his pockets, the cowboy turned and walked away into the darkness. And as he went, wherever his boots touched, a small shower of sparks glittered in his wake.

Jake caught his breath.

Stardust!

It was stardust!

He’d seen the stardust cowboy! The biggest and brightest and best of them all—the one his mom had always told him stories about, the one his dad had drawn him a picture of.

“He comes into your life when you least expect it,” his mom always said, “and invites you along on great adventures. The question is,” she went on, and her voice got deep and round and tempting, “are you brave enough to go with him?”

The cowboy hadn’t been waiting for Shane at all.

In Jake’s moment of greatest boredom, the stardust cowboy had come looking for him!

He shoved himself off the chair and hit the floor running, darted between dancers, bumping into them, muttering, “Sorry,” as he headed for the door.

Behind him he heard his mother’s shocked, “Jake Malone!”

“Come on!” he called back to her. “Come on, Mom! He’s here! It’s him!”

She’d know who he meant. She was the one who’d told him about the stardust cowboy in the first place. Every night when he was little his mother had held him on her lap and snuggled him close, her voice alive with excitement, as she told him stories of this special cowboy who gave you the chance to live your dreams.

And he was right outside now—if Jake could just get to him.

“Jake!” He heard his grandfather’s sharp voice call after him. Jake knew that tone. It was an order. It meant “come here.”

But he couldn’t obey. Not this time. He pretended he didn’t hear and slipped into the foyer. He wrestled with the heavy oak door and finally, desperately, wrenched it open. He clattered down the steps, jumping over the last three onto the sidewalk, searching eagerly in the darkness for the sparkle of stardust, for the silhouette of the cowboy who had come to bring him hopes and dreams and promise.

But the cowboy was gone.

Riley Stratton hated weddings.

So standing outside the reception of a couple of people he didn’t even know was an irritation right off. They looked so damned happy. So fresh and bright and cheerful—as if they had the world by the tail.

Riley sometimes felt as if he had the world by the hooves—and all four were about to stomp him into the dirt.

He had enough to deal with. He didn’t need a wedding as well.

You didn’t have to see it, he reminded himself. Just because Dori Malone’s neighbor had said that’s where she was, he hadn’t had to come running over.

It was just that he wanted to get it done.

He wanted to break the news about Chris, tell her about the ranch, get her agreement to sell, and head home, so that tomorrow his life would be back to normal again and he’d have nothing more to worry about than working his cattle.

And—incidentally—he wanted to see the boy.

The boy.

Riley had stood in the shadows when the wedding guests had come outside and flanked the steps while bride and groom ran down between them amid a shower of rice and birdseed and glitter. Everyone else had been watching the wedding couple.

Riley had been scanning the guests for a boy.

He’d be close to eight now. There had been several pictures of him in the small bundle of letters that had come last week in the mail. They had been part of what he supposed were Chris’s “effects.”

Until then it had been impossible to think of Chris as being dead. Impossible to believe that his brother wasn’t out there somewhere, driving like a maniac, playing his guitar like an angel, singing up a storm. Chris had been gone from home so long—ten years—and had come back so rarely, that Riley had long ago got used to not having him around.

But he hadn’t been able to think of his little brother as dead—not even when the very official, notarized certificate arrived from Arizona, where Chris had lived and worked for the past year.

Riley hadn’t really fathomed it until he opened the first of the thin bundle of envelopes rubber-banded together and five pictures had fallen out. Chris, he’d thought at first, because the little brown-haired, blue-eyed boy in the photos looked very much like his brother.

But it wasn’t Chris.

Jake was the name on the back of the photos: Jake at four months; Jake’s first birthday; Jake at three; Jake in kindergarten; Jake, a gap-toothed second grader.

Who the hell was Jake?

Scowling, Riley had fumbled the envelopes open and unfolded the letters—first one, then the next, until he’d read them all. There were five, written in a neat feminine hand, and they explained to Riley what Chris had never told him.

The boy—Jake—was Chris’s son.

That’s when Chris’s death had become real.

It was as though, if his brother had kept such a monumental secret for so many years, he didn’t really exist the way Riley had always thought of him.

And thinking of the vital, vigorous, hell-bent-for-the-horizon Chris dead and still as the result of a car wreck on a steep mountain road didn’t seem any stranger than thinking of his brother as the father of an almost-eight-year-old son.

The more Riley thought about it, though, knowing about Jake made sense of a lot of things Chris had done and said the past few years.

Jake must have been in his mind when, after their father’s death four years ago, Chris had declined to sell Riley his half of the ranch. “Nope, I can’t,” he’d said with his customary blitheness.

“Why the hell not?” Riley had been shocked, unable to understand why Chris would want to hang on to a ranch he’d been desperate to leave ever since he was fifteen.

“It’s my legacy,” Chris had said. “I might want to hand it on to my own kids someday.”

Riley remembered thinking that Chris settling down long enough to marry and have kids was a pretty unlikely prospect. He’d even said as much.

Chris had grinned. “You never know.”

Obviously, you never did.

Certainly, Riley hadn’t.

Back then Chris’s son must have already been four years old.

Two of the most recent letters thanked Chris for money he’d sent. And that explained a lot, too. Riley hadn’t understood why, if Chris was so determined to hang on to his share of the ranch, he’d been so unwilling to plow any of the profits of his share back in.

“I’ve got other priorities” was all Chris had said.

And all of Riley’s scornful comments about Chris’s fast-lane lifestyle had had no effect. All his common sense and logic had been wasted on his brother. At least that was what he’d thought at the time.

Now he realized that Chris really had had other priorities, other obligations.

You could have said, he told his brother silently. You could have told me you had a son.

But even as he thought it, he knew why Chris hadn’t. His brother would never have admitted to a son he wasn’t seeing, a son whose mother he hadn’t married, a responsibility he was dealing with in his own way, one that he didn’t want Riley haranguing him about.

And Riley would have harangued.

Responsibility, Chris had once complained, was Riley’s middle name. “Prob’ly was your first name. They just couldn’t spell it.”

In Riley’s opinion it wouldn’t have hurt Chris to have been a little more responsible now and then. In the instance of Jake, apparently he had been.

Sort of.

But he hadn’t left a will. It would never have occurred to Chris to make a will. He’d always considered himself invulnerable, unassailable, immortal. What thirty-year-old believes he’s ever going to die?

But he had died. And for almost a month Riley had thought he was Chris’s heir. The sole survivor. The owner of the Stratton ranch.

Legally he might be able to pretend he still was. Chris had never married the mother of his son. Marriage had never been a part of Chris’s plans.

He was, in his own words, “a rolling stone—lower case.”

He was a musician, like the uppercase ones, but the similarity ended there. Chris’s music had tended toward cowboy ballads and honky-tonk tunes. A lot of them he had written himself, and Riley knew little enough about music to be impressed.

But what had always impressed him more was Chris’s determination. From the time he’d been a little boy, Chris had had his sights set on the horizon—on moving out, moving on—and making a name for himself.

“I ain’t gonna be no two-bit cowboy,” he’d told Riley so often that it began to sound like the refrain to one of his songs.

Not like you. He hadn’t said it, but Riley could read a subtext as well as the next guy. Chris had never understood why Riley wasn’t champing at the bit to be gone. For years Chris had been counting the days until he graduated from high school and could kick the dust from his boots and head on down the road.

“At least you got as far as Laramie,” he’d said to Riley when his brother went away to college.

But college hadn’t lasted but three years. Right after Chris’s long-anticipated high school graduation and departure, their father had taken the fall from the horse that had crippled him.

There had been no one else to help out—no aunts, uncles, or cousins—just him and Chris. So Riley had come home.

Chris hadn’t.

“No way,” he’d said when Riley had finally tracked him down.

Chris didn’t bother with email. He rarely looked at his phone. That was the one thing he and Riley had in common.

“You’re not gettin’ me back there. You do it if you want, but it won’t just be while Dad’s laid up. It’ll be forever. You’re done for,” he’d told Riley flatly. “You go back, and you’re stuck. For good. You’re never gonna get away again.”

Riley hadn’t cared.

He’d always loved the ranch as much as Chris had hated it. And besides, he’d been fool enough to think that Tricia would come home with him.

Tricia . . .

No, goddammit, he wasn’t going to start thinking about Tricia tonight!

He had enough to think about, just contemplating what he had to say to Chris’s former lover—and to his child.

But he wasn’t going to be saying it at any wedding reception. He’d wait until they got home. It wouldn’t be that late. A responsible mother wouldn’t keep her kid out until all hours. And from her letters, Riley had determined however big a fool she’d been for loving his brother, in matters of parenthood, Dori Malone was definitely responsible and sensible.

He was glad. It would make telling her easier. And it would make her selling out to him a foregone conclusion.

He tucked his hands into his jacket pockets, and he strode away down the sidewalk toward his truck.

End of Excerpt