Start reading this book:

Share This Excerpt

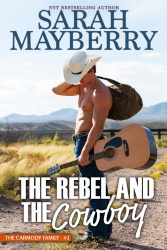

“I’m going to take art lessons,” Tuck said.

Jed McCall turned from the stove to stare at his nephew, as amazed as if Tuck had just announced he was going to run away and join the circus. As far as Jed was concerned, a circus would have made more sense. “Art lessons?”

Tuck nodded. “Felicity thinks it would be a good idea.” He lifted his version of the don’t-mess-with-me McCall chin and met Jed’s gaze, unblinking. He didn’t have to look up as far this year, Jed noticed. The boy was ten now and getting kind of lanky—not quite to the awkward stage yet, but close. Like a pup trying to grow into its feet. Jed remembered the feeling.

“Felicity thinks that, does she?” He banged the frying pan on top of the stove and slapped in a knife’s worth of congealed bacon grease. It sizzled and spattered. He cracked an egg and wished for an instant it was Felicity Jones’s meddling head.

His boss Taggart Jones’s new wife, Felicity, had been Tuck’s teacher last year. Obviously, even though Felicity had passed the boy on, she was still keeping her hand in—and her suggestions. In fact Jed liked Felicity—when she wasn’t meddling in his life. A pretty blonde with dimples to die for, Felicity had a smile that would curl a man’s toes and a heart as big as the Montana sky.

She’d come to Elmer only the year before, but it hadn’t taken her long to make an impact on the community. Especially on Taggart.

Jed had been as surprised as anyone when they’d got married last November. Still, he thought Taggart had made a good choice this time. After his disastrous first marriage, Taggart hadn’t wanted a woman in his life any more than Jed did, though for very different reasons—and he probably wouldn’t have one, either, Jed thought, if it hadn’t been for his meddling daughter, Becky.

What was it with women? he wondered now, grimacing. He cracked another egg next to the first and slopped some of the melting grease over both.

“Well, good for Felicity,” he said after a moment’s reflection. “An’ she’s probably right, too,” he added honestly. “You do have talent. But where the heck does she think you’re going to get art lessons around here?”

Elmer, Montana, seven miles away, was the closest town. And while Elmer was useful for getting your horse trailer welded or buying milk and bread, it wasn’t exactly the hub of the Western cultural world. Among its 218 or so inhabitants, art teachers were not exactly thick on the ground.

Now if Felicity had suggested acting lessons . . .

Thanks to the sudden influx of rich California yuppies, you couldn’t throw a rope these days without lassoing a movie star, Jed thought wryly. But art teachers? They didn’t make enough money to live around here.

Neither did he, come to that. If his foreman’s job hadn’t come with housing, Jed could never have afforded to stay on in the valley. As it was, he made enough to get by, but not enough to pay an art teacher! He shook his head at Felicity’s well-meant but lame-brained notion and scooped more grease over the eggs, frying the tops without turning them over.

“It won’t cost anything,” Tuck said as if reading his mind.

“You got an art teacher up your sleeve, do you?”

“Felicity does.” Tuck paused. “Brenna.”

Grease spattered against Jed’s hand. He didn’t feel it. He didn’t feel anything—except the shaft of cold white panic shooting straight through him, from his ears to his brain to his groin and straight on down to his toes.

“Brenna Jamison,” Tuck clarified, as if there could be another. “You know her, don’t you? Old Mr. Jamison’s daughter. The artist from New York. Felicity asked her.”

Tuck looked at him eagerly, but Jed didn’t reply, just stood, riveted, the grease spattering on his hand.

“She said Brenna was an artist, not a teacher really,” Tuck went on when Jed still didn’t speak, “but that talent like mine should be encouraged—and, well, what did we have to lose?” Finally Tuck edged around so he could see his uncle. “You’re burning those eggs!”

Jed moved at last. Jerked, really. Yanked his burned hand back, shaking it, scattering drops of hot grease everywhere, swearing under his breath.

Tuck jumped away. Jed scraped the eggs out of the pan and slapped them onto a plate. His hand was shaking. He flattened it on the countertop. Swallowed. Dragged a desperate breath up from his lungs.

“What happened?” Tuck demanded, watching his uncle worriedly.

“Nothin’ happened.” It was hard to even form the words. They were apparently unconvincing in any case.

Tuck was looking at him still, his expression concerned. “You okay? You sure?”

Jed gave him a hard look. Of course he was fine. It was the surprise, that was all. He took another deep breath, then another. And another.

Brenna. The name pounded in his head.

“So,” Tuck said after a moment, apparently convinced now, his concern gone, his voice vibrating with cheerful little-boy eagerness again. “Brenna Jamison’s gonna teach me! What do you think of that?”

“No,” Jed said.

There was a moment of disbelieving silence. Then Tuck said, “No? What do you mean, no?”

“Just no.” Jed studied his fingers, then flexed them slowly. Calmly? Ha.

“But—”

Jed’s head snapped around and he fixed his nephew with a glower. “I said no. You don’t need art lessons!”

Tuck pressed his lips together in a tight line, looking exactly like Jed’s kid sister, Marcy—Tuck’s mother—had looked whenever someone had tried to stand in her way. “That don’t make sense. You just said Felicity was right. And Brenna will teach me for nothin’. She told me so.”

It was like a punch in the gut. “You asked her?”

“Felicity did, this afternoon when Brenna came to school to see my stuff. She liked it. She said so,” Tuck said firmly when Jed looked doubtful. “We’re starting with drawing, ’cause I’ve done some already. I showed her when she dropped me off.”

Jed’s fingers sought the spatula, strangled it. “Dropped you off where?” A pause. “Here?”

“How was I gonna get home otherwise? I missed the bus. I figured you’d be out on the range. And here’s where my drawings are.” It was perfectly logical to Tuck.

“I was working in the barn,” Jed said tightly more to himself than to the boy. God, he could have walked out and run right into her!

If Tuck noticed the non-sequitur, he didn’t comment. “She didn’t mind bringin’ me. She wanted to see my drawings.”

Jed licked suddenly parched lips. “You brought her in the house?”

Tuck blinked at his tone. “She isn’t Madger the Badger, you know,” he said, guessing wrongly what Jed’s objection was. “She doesn’t care how we live. Besides we cleaned up good for Madger just th’other day. It doesn’t look too bad yet.”

Madger the Badger was Madge Bowen of some department of bureaucratic folderol. She’d been nosing around since last spring, sicced on them by some do-gooding yuppies who thought a hard-riding, tough-minded, simple-living cowboy was a questionable influence on a growing boy. Up until a minute ago she was the last person Jed ever wanted in his house nosing around. He hadn’t considered Brenna a possibility.

“She liked my drawings.” Tuck jerked his head toward the wall where they hung. “She said I had a lot of potential and she’d be pleased to teach me. So what do you think of that!”

Jed thought he was being sucked into quicksand. He glanced toward the spot above the table where he’d hung half a dozen of Tuck’s pencil sketches of last spring’s branding. They were framed in rough wood that he had knocked together not exactly professionally, and they were the best thing in the room.

Brenna had been in this rough, bare room? She had seen not only the sketches, but the worn rug and sparse furnishings in the two-room cabin he and Tuck called home? Jed felt a hot curl of shame begin to burn inside him. Would she think he couldn’t provide better than this? That he had nothing more to show for a dozen years than two rooms that didn’t even belong to him?

“She didn’t notice the house,” Tuck was saying earnestly. “She isn’t like Madger, pokin’ her nose in everywhere. She just looked at my drawings. I wanted her to know she wouldn’t be wastin’ her time teachin’ me. She’s pretty famous, you know.”

Jed knew. The whole valley knew. Hell, most of the Western art world knew all about talented artist Brenna Jamison. The pen-and-watercolor paintings she made of her Montana ranch heritage were famous far beyond the Shields Valley. In fact they’d propelled her clear out of the state in which she’d been born. She’d gone away to art school eleven years before, and she hadn’t been back—except for the occasional visit—until her old man had had a stroke in July.

Jed had heard she was here to stay.

He profoundly hoped not.

But according to Taggart, she was determined to take over at least until ol’ Otis could run the place himself again.

“Got her work cut out for her,” Taggart had said, shaking his head. “I don’t think ol’ Otis has been doing much in the way of running things for the last year or so. Can’t see him bouncin’ back.”

It wasn’t his business, so Jed had only grunted a reply then. He grunted again now. What Brenna Jamison did or didn’t do wasn’t any of his business. Except if it came to teaching Tuck!

“I gave her the ones I drew of you an’ Taggart at the bull-riding school,” Tuck was saying. “Remember them?”

Jed remembered. He often helped out at Taggart’s bull-riding schools, running in the stock, doing a little bullfighting, keeping things moving, and usually Tuck came along and played with Taggart’s daughter, Becky. But over the past year, maybe because he was growing out of playing with girls, Tuck had taken to watching the bull rides—and drawing what he saw. The sketches were wonderful. Quick, fluid sketches of animals and men in motion. In surprisingly few strokes Tuck seemed to be able to catch the tension, the intensity, the dirt and sweat and, sometimes, the blood.

There was one in particular, Jed remembered—of himself—the one time he’d let Noah and Taggart tease him into riding a bull again for the first time in at least five years.

“Like riding a bike,” Taggart had grinned. “You don’t forget.”

Maybe not, but your reactions weren’t all they used to be, either. And Jed had ended up on his butt in the dirt. Tuck had captured it deftly.

Jed used to get the sketch out and look at his own stunned expression every time he took it into his head to do something stupid. It had kept him on the straight and narrow pretty successfully over the past year.

Now he said, “You gave those sketches to Brenna? All of them?”

“She asked and I said sure.”

“I didn’t!”

Tuck’s eyes widened. “They weren’t your drawings.”

“No, but—”

Was he going to say, I was in one of them? He tried to get a grip. Maybe Brenna wouldn’t recognize him. Maybe she wouldn’t care even if she did. Of course she wouldn’t! Why should she? He didn’t matter to her anymore. He was nothing more than a broken-down old cowpuncher from her past. Just because he’d once been fool enough to think he was man enough to marry her . . .

“What’sa matter with you?” Tuck demanded now, staring up at his uncle with unnervingly steady hazel eyes.

Jed wasn’t going to win this battle and he knew it. Tuck was right; they were his drawings. Art was his talent. It was just that . . . Damn it!

He braced his palms on the counter and slumped, letting his head drop forward. He shut his eyes and tried to think, tried to be clear and calm and dispassionate.

It wasn’t working. It rarely did. That was why he needed the bull-riding sketch. So he had a visible reminder of what an ass he could make of himself because he really wasn’t the clear, calm, dispassionate type.

People thought he was, because he was quiet. They were wrong. He was quiet not because he was cool and dispassionate, but because if he didn’t keep a lid on himself he’d blow sky high. Like now.

“Nothing’s the matter.” He forced the words past his lips. He shoved his hand through his hair, then kneaded the knotted muscles at the back of his neck. Nothing’s the matter. Maybe if he said it often enough . . .

“You won’t have to stop work to take me or pick me up.” Tuck was back at the art lessons, fielding objections before Jed could even voice them. “Felicity checked an’ I can take the school bus that goes out by Brenna’s ranch after school once a week. An’ Brenna said she’d bring me home after.”

Jed took a breath. “I won’t be beholden to her. To anyone.”

“We’re already beholden . . . to everyone,” Tuck pointed out logically. “How many times have you left me at Taggart’s while you went away for the weekend? How many times have Tess and Felicity made us supper?”

Jed gritted his teeth. “When I go away for the weekend, I’m on Taggart’s business buyin’ cattle. You know that.”

“All weekend?” Tuck’s voice was mild, but his brows arched speculatively. He reached over and picked up the matchbook that lay on the counter by the stove. It said Lucy’s in big red flowing letters and in smaller equally red ones, where the ladies are lookers.

Jed snatched it out of Tuck’s hand and stuffed it into his pocket. He picked up the plate of eggs and shoved them at his nephew. “Your supper’s gettin’ cold.”

Tuck took the plate, contemplated it, then set it back on the counter and made a face. “You have ’em. I’m sick of fried eggs. Anyway, I ate a roast beef sandwich at Brenna’s.”

It was the last straw.

Jed picked up the plate and crashed it into the sink, turned on his heel and stalked out of the cabin. He didn’t bother to close the door.

It was the only bit of good judgment he showed. If he had shut it, they’d have heard the slam clear down in Elmer.

He didn’t look like his uncle. He had red hair and freckles and hazel eyes that were warm and friendly. He was warm and friendly—like a puppy, eager to show off, eager to please. Eager to learn what famous artist Brenna Jamison had to teach him.

And famous artist Brenna Jamison had agreed to teach him, though she’d never taught anyone in her life—because Tuck McCall was talented, and he was determined, and he was enthusiastic. But most of all, let’s face it, because he was all those things—and he didn’t look like his uncle.

She was very much afraid that if he had resembled Jed, she would have been tempted to say no.

She couldn’t have spent an afternoon a week, not to mention the occasional Saturday, in close proximity to a boy who was the spitting image of Jed McCall.

And what does that say about your maturity? she asked herself archly as she prowled around the big old ranch house she’d grown up in.

It wasn’t a question she wanted to answer. It was one that, up ’til now, she’d been grateful she hadn’t had occasion to ask. In the two months she’d been back on the ranch, Brenna had glimpsed Jed only twice—and then just from a distance, never to speak to. Which was fine with her.

What would she say to him, anyway?

What did you say to the man who said he wanted you, that he loved you, and then, the very next day, wouldn’t even look at you, who walked out of the room—and your life—without looking back?

There was nothing to say. Especially not now. And she was foolish to be fretting about it. Brenna was quite sure he wasn’t fretting.

He probably didn’t even remember she was alive, she thought, sinking into the old leather-covered armchair by the piano. It had been eleven years, after all, since their . . . since their . . . since their what?

Declarations of undying devotion?

Well, maybe hers had been. Clearly Jed’s hadn’t. To be honest, other than those words and the few kisses and feverish touches, which had never seemed enough, they hadn’t had anything. Not by twenty-first century standards at least.

At best she’d had an adolescent crush and Jed had had . . . male hormones.

She didn’t know what else to call it. He’d been twenty-one years old—at the height of his masculine urges—and, plain and simple, he’d had the urge for her.

At least until Cheree had come along.

Brenna closed her eyes. It did no good. The memory was burnt into her mind: Cheree, the beautiful Cheree, the worldly Cheree, her brand-new stepsister, who had been everything that the unsophisticated, terminally naive Brenna had not.

The situation was so clichéd she would have laughed—if it hadn’t hurt so much.

“What a man he is!” Cheree had said later, smiling knowingly. Brenna had wanted to die.

If she could find any consolation at all, it was that Jed hadn’t married Cheree, either, though he’d obviously shared more than a few feverish kisses with her stepsister. Still, he apparently hadn’t loved her stepsister any more than he’d loved her.

Or anyone else, apparently.

Cheree had long since settled down and married a stuffy Philadelphia banker. But Jed was still a footloose bachelor at thirty-two.

Not that Brenna cared.

Not on your life. Brenna Jamison was well and truly inoculated against the likes of Jed McCall.

He could spout sweet nothings for hours on end and she’d turn a deaf ear. He could dance naked on a table top and she’d look away. He could – well, if he really did dance naked on a table top, she might peek. But purely for academic interest. She was an artist, after all. Human anatomy was grist for her mill.

Uh-huh.

Oh, Brenna, stop it, she counseled herself. She flung herself back up out of the chair and raked her fingers through her hair. Pins scattered across the floor as she shook out the dark auburn twist she’d anchored against the back of her head before she’d driven into town to meet Felicity and Tuck. Brenna shook her head, trying to relieve the pressure she’d felt all day. It was just because of her hair, she’d told herself. She’d pinned it too tight.

She knew better. It was because she might have seen Jed. She hadn’t really expected him to show up after school at her meeting with Felicity and Tuck, and she’d breathed a sigh of relief when he hadn’t.

But then, still playing with fire, she’d dared take Tuck home after. As she’d driven up the narrow track that led to the cabin where they lived, she’d spotted his truck parked by the barn and her mouth had gone dry and her palms suddenly damp. The truck didn’t mean he was there, of course. Chances were he was out on horseback, bringing in Jones’s herd.

But he might not have been, and she knew it. He might actually have been there when she’d dared accompany Tuck into the house.

He hadn’t been—thank God. What would she have said? Remember me?

Brenna pressed her palms against her heated cheeks. Stop it, she commanded herself once more. It’s over. Done. He wasn’t there. And even if he had been, he’s nothing more than a part of the past. You’ve got lots more important things to think about—and worry about—than Jed McCall.

Like her nursing-homebound father who was chomping at the bit to get out of that “consarned prison,” as he called it, and come back to the ranch. Like a ranch with eight hundred head of Simmental beef cattle that needed to be sorted and shipped within the next month with no one competent to manage it. Like the hands she had hired—Sonny and Buck—two of the sorriest excuses for cowboys she’d ever met.

Every other Saturday, which was to say after payday, Sonny and Buck went on a bender and were still so bent on Sunday night that unless Brenna went and got them, they never made it back to the ranch.

So far every two weeks, she’d done so, because they at least had a rudimentary knowledge of riding and roping, which was more than she could say for the ex-surfers that Job Service sent out. Now there was a work ethic for you, she thought grimly.

So she was stuck with trying to keep Sonny and Buck sober until the cattle were sorted and shipped next month. After that, she could breathe again—and start trying to get the rest of her life in order. God knew she needed to.

And to start once more to paint.

With the ranch, which hadn’t had anything repaired in a year or more from the look of things, and with running back and forth to Bozeman every other day to see her father, she’d been far too busy to give it a thought. She hadn’t painted in a month.

She didn’t even take a sketch pad with her when she went out riding anymore. Her artist’s eye no longer sought the play of light and shadow, line and curve, but instead looked for signs of pink eye and black leg and scours. Loren, her agent, was getting impatient.

“It’s all well and good,” he’d said in his eastern-boarding-school accent just last week, “for you to go back to Montana and dip into the well of your inspiration. You don’t have to drown in it.”

Brenna didn’t want to drown in it, either. She wanted to make it a success, to prove that she really was the child of this land that she’d always believed she was. She wanted to show her father that she could do it. She wanted—needed—a future here. Not in New York.

“You want to stay there?” Loren had been aghast at the thought.

“Yes.”

“But—”

“Don’t try to understand,” she’d said gently.

“Artists,” he’d muttered. “Raving eccentric twits, all of them.”

Brenna had smiled then. “Something like that,” she murmured now.

But she would do it or die trying. Now, after two months of eighteen hour days, she thought death might win.

It wouldn’t—couldn’t—she vowed—because she needed the ranch for herself—and for her child.

That was what really kept her going, what kept her fighting when by rights she should have given up long ago: She was going to have a child.

She pressed her hand against the curve of her abdomen, waiting, then smiling as she felt the stir of the child within. She always smiled whenever she felt those soft fluttery movements. They felt like butterfly wings. She remembered watching a pair of butterflies hovering near the geraniums on the terrace of their New York City apartment the day she and Neil, her husband, found out she was pregnant. He had been thrilled. She had been scared to death. It was what she’d wanted, what she’d hoped and prayed for, and yet . . .

“They fly from here all the way to Mexico,” Neil had said, his voice soft. “Yucatan, I think. Can you imagine that?”

“They don’t all make it,” Brenna had replied, preoccupied with her own fears.

Neil had smiled and shaken his head, then reached for her hands, pulling her down next to him on the lounger and looking deep into her worried eyes. “The strong ones do, Brenny,” he’d assured her. “The strong ones do.”

Brenna needed to believe she was a strong one now.

Neil had died in June. Her father had had a stroke in July. She was first a widow and now a rancher. And in three and a half months she was going to be a mother. She had her work cut out for her.

So why in heaven’s name was she taking on another commitment—especially one with the last name of McCall?

Because art was in her heart, pain was in her veins, and another McCall had once been in her soul.

An exorcism then? Was that what she was hoping for?

She picked up the one sketch that had positively leapt out at her from the ones Tuck had let her take home.

It was a rough drawing of a cowboy on his rear in the dirt, stunned by a fall from the bull in the background. In its untutored lines she saw resignation and determination. A man who had tackled something too strong, too big, too formidable to handle and knew it. A man who would—tomorrow or next week—do the same thing again.

Jed.

She hadn’t seen him up close in almost a dozen years. She knew him in an instant, in a child’s drawing.

At the sight, her fingers had clenched. Her stomach had twisted. Her heart had lurched—the way it always had whenever Jed McCall came into her range of vision.

For years she’d assured herself that Jed had been nothing more than a youthful infatuation—one she was well off never to have tested the limits of.

Oh, Brenna, you fool. The intensity of her reaction was enough to prove that she couldn’t have been more wrong. The infatuation—if that was indeed what it was—had survived a dozen years.

An exorcism? Please, God, yes.

She was a successful artist. She had been a wife. She was going to be a mother. It was time—and she was woman enough at last—to face her unfinished business with Jed McCall.

Perversely the art lessons Jed couldn’t prevent won him a point or two with nosey Madge.

“Well, good,” she said when she came to visit and Tuck told her about them. “I’m glad to see your uncle recognizes your talent.”

Tuck tactfully refrained from mentioning that his uncle’s only contribution to the advent of art lessons had been his objections. “Oh, yeah,” he said, grinning and giving Jed a significant look from beneath the red fringe of his hair.

Jed scowled. “Don’t you have chores to do?”

Shrugging, Tuck took himself off to the barn.

When he’d gone, Madge looked at Jed over the tops of the half-glasses that made her look like a near-sighted owl and ruffled her papers as if they were feathers. “Finally something positive I can tell them.”

Jed supposed he should be glad one positive thing was coming out of the blasted lessons because it sure wasn’t his state of mind.

For the past three weeks he’d been treated to tales beginning with, “Brenna says . . . ” and “Brenna thinks . . .” and “When Brenna and I do thus-and-such . . .” more times than he wanted to count. It had been all he could do not to stuff cotton in his ears or a gag in Tuck’s mouth.

Now they’d been at it four weeks and when Tuesday afternoon arrived, Jed prepared himself for another onslaught.

He stood just inside the barn, out of sight, waiting for Brenna to drop Tuck off. He could’ve gone back to the house, but he didn’t want to be walking across the yard when they came and they were usually there by five-thirty.

But five-thirty had come and gone. Now it was well past six. Jed prowled out from the barn and scanned the road, wondering where they were.

“Madge would be proud,” he muttered.

Madge’s social worker heart was delighted to discover any paternal feelings Jed could muster. He didn’t know why she thought he was so damned deficient.

Hadn’t he taken Tuck on when there was no one else at all?

When Marcy had died, he hadn’t hesitated to take the boy, even though he didn’t have the faintest notion how to raise a child. But they’d rubbed along okay, he and Tuck. It had been over two years now, and they were fine. It had just been their bad luck for Tuck to miss the bus and be walking home in that winter storm and get picked up by a bunch of meddlers who believed in governmental solutions to family problems.

Jed ground his teeth the way he always did when he thought about it. Then he braced his hand against the doorjamb and squinted into the distance, hoping that glint was the reflection of the setting sun hitting Brenna’s windshield as she wound her way up the hill. But the truck kept moving west and didn’t turn onto the narrow track that led off the county road up into the hills where their cabin sat.

6:20 and still no Tuck.

Jed’s fingers played with the cell phone tucked in his pocket. No, he wasn’t going to call. Tuck would turn up.

The phone’s sudden ring sent him jumping almost out of his skin. He scrabbled with the phone, fumbling to answer. It was Tuck. “What?” he barked.

Over a line of static he heard Tuck say, “Can you come help?”

“What’s wrong? Where are you?”

“At Brenna’s,” Tuck said cheerfully. “We were bringin’ down some cattle. The truck died an’ we tried to find Buck an’ Sonny. But Buck’s drunk an’ we can’t find Sonny an’—”

“Whoa,” Jed said. “What cattle? What truck? What about the damned art lessons?”

Wasn’t that what he was suffering all this Brenna business for?

“We didn’t get around to ’em today,” Tuck said, unconcerned. “When I got here, Brenna was bringin’ in some cattle. She said she’d stop, but I could tell she needed to be doin’ the cattle more. She’s shipping Friday and they ain’t hardly brought any of ’em down.”

“Haven’t brought,” Jed corrected. He might have said ‘ain’t’ himself in the not too distant past, but now he was a role model.

“So can you?”

“Can I what?”

“Come help,” Tuck repeated impatiently.

Come help. Just like that. Jed shut his eyes.

“I figured you’d want to,” Tuck added after a good thirty seconds of silence. “Not to be beholden an’ all. An’ because it’s a neighborly thing.” He quoted Jed’s own words in far different circumstances.

It was, of course, but—

Help Brenna? See Brenna? Talk to Brenna? Oh, God.

Jed worked his tongue loose, then swallowed, hoping for just a little spit so’s he could talk. “Just . . . fix the truck, you mean?”

“Well, maybe tomorrow you could bring down some cattle. If Buck’s still drunk, I mean, an’ she still can’t find Sonny.”

“I’ve got a job, you know.”

“But Taggart’s shipped already. He wouldn’t mind. He’d prob’ly even help.”

He probably would. And Taggart wouldn’t feel near the desperation that Jed was feeling. “I’ll call him,” he offered.

“But you’ll help, too,” Tuck insisted. “You’ll fix the truck, won’t you? I told Brenna you would. Didn’t you want me to?”

“No! I mean, yeah. Of course. I—” Jed dragged in a desperate breath “—I’m on my way.”

It was just fixing a truck, he told himself, climbing into his own battered pickup. Nothing he hadn’t done before. God knew he’d fixed this one often enough. As for the cattle . . . well, maybe Buck and Sonny—whoever they were—would be back on the job by morning.

And if not . . .

If not—Jed shrugged tense shoulders against the worn seat of the pickup—he’d move the cattle. It was what he did every day, after all. Just his job. No big deal. Brenna being around wouldn’t make a bit of difference.

It was pretty amazing the way a guy could lie to himself.

End of Excerpt